Disaster psychiatry is an area of practice that seeks to apply mental health knowledge and expertise to the setting of disasters. Ministering to the psychological needs of a disaster-stricken community in the acute aftermath of a disaster is distinctly different from what it is required in dealing with the long-term aftermath months or years later. The context of service delivery, the relevance of psychiatric diagnosis, the clinical interventions, and the personal challenges for the psychiatrist are all vastly different from the rest of psychiatric practice. In order to help psychiatrists judge whether to engage in acute disaster psychiatry or prime them for how to engage in it, this paper reviews both the rewards and challenges of engaging in this work. Ultimately, the challenges outnumber the rewards, but the disaster psychiatrist sees rewards even in the challenges.

Introduction

Disasters are traumatic events that overwhelm a community. Disaster psychiatry is the professional application of mental health knowledge and expertise to the unique setting of disasters10). In the United States, disaster psychiatry is generally thought to have been first recognized as a unique area of practice following Erich Lindemann's publication on grief following the fire that that occurred at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub in Boston in 1942 and claimed 492 lives, making it one of the deadliest fires in U. S. history13). However, decades later, disaster psychiatry remains an “extra-curricular” field as there are no known academic departments or divisions of psychiatry in the U. S. , although such a department does exist at Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan. There are also no formalized training fellowships in the U. S. except for one at the Uniform Services University in Bethesda, Maryland in the U. S. (https://www.usuhs.edu/psy/fellowships). Training in this highly specialized area must be sought out via conferences or reading. There are thankfully many excellent textbooks or manuals on disaster psychiatry19)22).

Indeed, it can also be said that for most psychiatrists (and other mental health professionals) it is an “accidental” area of practice, as their involvement often occurs based on the happenstance of a disaster striking a community where they live, or they have a pre-existing personal or professional connection. Therefore, many psychiatrists learn disaster psychiatry “on the fly” from the experience of being thrown into a disaster and being called upon to apply their prior psychiatric training and expertise to a disaster-affected community. To the extent that they are able to seek out training or reading on the subject, it is “just in time” learning.

This paper describes the broad themes in disaster psychiatry in order to efficiently orient the many psychiatrists who seek to rise to the challenge of a disaster without the benefit of prior training or experience. It may also be helpful to anyone contemplating embarking on disaster psychiatry as part of their career. The focus will be on the acute aftermath of a disaster, as this is the period that most truly distinguishes disaster psychiatry from more conventional psychiatric practice. This is usually the period in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, from days to weeks, whereas the post-acute period encompasses weeks to months to even years12). It is when the “dust” has begun to settle. The themes are drawn from the author's experiences as a part-time disaster psychiatrist over the last twenty years, including as part of the founding leadership of an organization known as Disaster Psychiatry Outreach, supplemented by the scientific literature whenever possible. They span the experience, techniques, ethos, and aspirations of practicing disaster psychiatry and will begin with an enumeration of the rewarding aspects of practicing disaster psychiatry, followed by a discussion of its professional and personal challenges.

I. Rewards

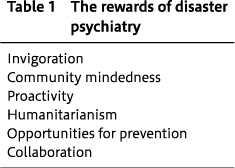

Disaster psychiatry boasts a number of rewards, as listed in Table 1 and described below.

1. Invigoration

It should be stated at the outset that responding to a disaster is energizing, a truth that can feel like a confession. Disaster conjures many feelings, many distressing, but compared with the rhythm of daily life and as long as one has not sustained personal loss, it sparks a rush of adrenalin. With the possible exception of emergency department-based psychiatry, psychiatric practice rarely occurs in such an action-oriented environment. The flashing lights, perpetual motion of responders, and pop-up press conferences are a world apart from the psychiatrist's consultation room. Although it is difficult to find any psychiatrist who has put this in print, this departure from their largely staid professional lives is alluring. This was hinted at when a close colleague wrote the following about dropping everything and rushing with the author and other team members to post-earthquake El Salvador in 2001: “The priorities of a continued research program with its ups and downs seemed mundane in comparison to the life-and-death struggles of such a disadvantaged population of people.”6)

The invigoration of disaster response is mentioned as a rewarding aspect of disaster psychiatry, but it should also be mentioned that it can pose a risk for some. If psychiatrists wanted such professional stimulation, they likely would or should have chosen a different field of medicine or even a different field from medicine. Thus, not all psychiatrists thrive or even function adequately amid the hubbub of a disaster response, nor do they enjoy it.

2. Community-Mindedness

Psychiatrist-clinicians largely work with patients, usually individually and sometimes in groups. Psychiatrist-researchers largely work with research subjects or test tubes. Although American medical education has become more and more focused on teaching the social determinants of health, a major curricular transformation has yet to occur. 7)Thus, physicians in general are trained to focus on individuals rather than communities or systems. It is therefore not surprising that American psychiatrists who are interested in communities have taken to carving out their own professional niche via a professional organization, the American Association of Community Psychiatry (www.communitypsychiatry. org).

However, with the emerging emphasis on social determinants of health, it can be argued that the field of psychiatry ought to focus more on these determinants and on the communities in which psychiatrists practice. Acute disaster psychiatry, with its emphasis on working outside of our usual offices and organizations, offers such an opportunity. Physically being out in the community can offer disaster psychiatrists both the opportunity to learn more about their communities and also the chance to experience those communities other than through the eyes of our patients. Responding to a disaster is a unique chance to connect in a very direct way with what in prior versions of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders was called “Axis IV”, psychosocial and environmental stressors2).

3. Proactivity

Bringing ourselves and our services to people is outreach5). One dictionary defines outreach as “the extending of services beyond current or usual limits”15). Indeed, disaster psychiatry offers the chance to bring psychiatry to people rather than the much more customary stance of waiting for people to come to us. Under usual circumstances, there are any number of barriers in the way of access to our services, especially the stigma around doing so. However, outreach, although not necessarily a direct response to stigma, is at least a way to circumvent or mitigate its effects.

Indeed, if there is a heightened need for mental health support after a disaster, there are also many more than the usual barriers for seeking care. Survivors' lives are turned upside down by death, injury, illness, displacement, and unemployment, and with so many concrete needs, thinking about one's emotional life may get de-prioritized even more than usual. Sitting back in one's office waiting for disaster survivors is a lonely business.

The outreach of disaster psychiatrists is especially likely to be successful and necessary not simply because they have located themselves within the disaster affected community, but also because it is occurring at a time when attention to mental health is more acceptable. Consider that although depictions of disaster in the media often involve scenes of destruction (i.e., houses flattened by a tornado), they at least as often show survivors in distress (i.e., a suddenly homeless family crying amid those ruins). Emotions are raw in the immediate aftermath of disasters and disaster psychiatrists therefore can expect an uncommon welcome from affected communities. We often spend our time inviting, even imploring, our patients to feel and identify their emotions, but with disasters, the emotions are upfront and our presence in the community make us a timely resource.

4. Humanitarianism

Disaster psychiatry affords the chance to marry the rewards of traditional psychiatric practice with the rewards of humanitarian work. Humanitarianism involves responding to human suffering and realizing human fulfillment by acting in a virtuous manner based on compassion, empathy, or altruism1). Bound up in the modern understanding of humanitarianism are its voluntary nature, focus on emergency aid, and belief in ministering to all human suffering without prejudice23). As acute disaster psychiatry inevitably, and properly, entails voluntary action under dire circumstances, it is very much founded in a humanitarian ethos. To the extent that its “patient” is a community rather than an individual, disaster psychiatry in its truest sense must be egalitarian-anyone is a potential beneficiary of the disaster psychiatrist's services simply because they live in or are helping out in the disaster-stricken community.

5. Opportunities for prevention

Psychiatric care typically involves tertiary prevention because psychiatrists diagnose and manage psychiatric disorders. It is not a field oriented towards primary prevention, i.e., intervening before mental illness occurs or even secondary prevention, i.e., screening to identify emerging illness early before it worsens. This unfortunately puts the field at some distance from concerns about public health. However, disaster psychiatry is different because it is premised on the belief that not only is reaching out to a stricken community the compassionate thing to do, but it is also potentially preventative. Although studies must yet gauge the reality of this aspiration, it is a reasonable belief that early and thoughtful intervention by psychiatrists and other mental health professionals in a potentially traumatic situation can only serve to mitigate suffering and thereby reduce the chances that expectable human suffering evolves into the three most common post-traumatic psychiatric disorders--major depressive disorder (MDD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and alcohol use disorders (AUD). Disaster psychiatry ought to be an exhilarating chance to prevent traumatized individuals from showing up at our clinics in the future, as disasters are the most public of traumas.

Disasters are also opportunities to treat people who should have shown up at our clinics before the disaster. Prior psychiatric problems, and especially under- or untreated ones, are a well-validated risk factor for developing post-disaster mental health problems, as are having pre-event problems of living (i.e., relationship or workplace problems) 12). The highly emotional post-disaster environment where having psychiatric issues is much more acceptable and the easier access to psychiatric care due to on sight disaster psychiatrists may enable pre-existing mental health problems to be captured and addressed.

6. Collaboration

Although perhaps the least of the rewards of disaster psychiatry, the chance to collaborate with fellow responders offers an opportunity to get to know an entirely different professional world. In the U. S. , the vast number of federal, state, and local agencies that respond to a disaster are often referred to as the “alphabet soup” of responders because of all of the acronyms they go by (i.e., “ARC”=American Red Cross or “FEMA”=Federal Emergency Management Agency). If the psychiatrist normally works in an organizational setting, such as a hospital or a clinic, then working in disaster response thrusts them into an entirely different team where they may well be the only mental health professional or even health professional. If the psychiatrist works in a private practice, then they trade their usually more solitary practice for team-based efforts.

Although a recent meta-analysis revealed considerably more acceptance and de-stigmatization of psychiatry and psychiatrists by the public during 2000-2015, the investigators also suggested that the public sees psychiatrists as more suited to prescribing medication than listening and talking3). Another study revealed that 90% of medical faculty at medical schools across Europe and Asia said they felt psychiatrists were not good role models for medical students21). Psychiatrists getting into the “trenches” of disaster-stricken communities with other physicians and responders can project a powerful image of compassion and activism.

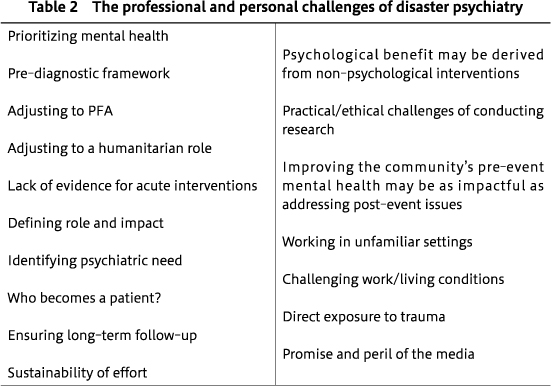

II. Challenges

There are many challenges posed by disaster psychiatric practice and they far outnumber the rewards, as reflected in Table 2. Indeed, some are the mirror image of the rewards, perhaps none more so than the challenge of prioritizing mental health. Disaster may be a unique opportunity to be proactive, but as important as it is for the psychiatrist to get out into the disaster affected community, the welcome may be uneven. Disaster response agencies will be greatly reassured by their presence, which can have the effect of erecting an invisible but palpable “trauma tent” over the scene, a psychological space where the heightened emotions of the moment are safely felt, expressed, and shared11).

However, the survivors of a disaster have much to contend with beyond their mental health, an invisible dimension of life that too often and too easily gets overlooked even in the best of times. The disruption and destruction of disasters usually thrusts countless new and unexpected tangible needs into the laps of governments, communities, organizations, families, and individuals, and tangible needs should come first. This is the fundamental idea of Maslow's so-called hierarchy of needs, which describes how humans are fundamentally motivated to address the most basic of needs, such as safety and physiological needs, before turning to higher order needs such as those of belonging and self- confidence14). Although a time of unavoidably heightened emotions may create a window for psychiatrists to make an impact, unlike at any other time, it is also a time of simply heightened needs, many of which can, and often should, divert attention from explicitly addressing mental health.

Indeed, it is fair to say that no psychiatrist should involve themselves in responding to a disaster who does not recognize the primacy of basic needs like safety, shelter, and nourishment, and who is not prepared to address them. It can even be said that an appreciation of this primacy constitutes a necessary ingredient for being a good psychiatrist in everyday practice. However, although the everyday psychiatrist can usually leave it to others to address basic needs while they ply their specific psychiatric skills, the disaster psychiatrist has no such luxury. They must face the challenge of adjusting to a humanitarian role. If as we said earlier humanitarianism involves responding to all human suffering without prejudice, this not only means assisting all people, but also attending to all of their needs. For example, while the team was on the earlier mentioned disaster psychiatry mission to earthquake-stricken El Salvador in 2001 and another earthquake struck while they were en route to a psychiatric hospital, they diverted and went to the town at the epicenter of the second quake. When they arrived at the town's hospital, they adjusted their efforts. It was no time for anti-depressants or psychotherapy as pre-existing patients were being evacuated into a sunbaked plaza to make room for the newly injured. They instead went around offering water to patients who were able to drink or even placing I. V. lines for those who could not. The best disaster psychiatrists are those who consider themselves people first, physicians second, and psychiatrists third.

For the psychiatrist to function as such in the third role in the acute disaster setting, identifying individuals with psychiatric needs will also pose a challenge because they are not typically announcing themselves as such. The proactivity that can be a rewarding part of disaster psychiatry means that “case finding” is usually needed. Although every disaster setting is different, if there is an array of services set up for survivors and community members, disaster psychiatrists will need to integrate into them. This may involve setting up a “booth” and circulating among other service agencies to let them know, often repeatedly through “daily rounding”, of the availability of psychiatric services. The latter is especially important as other responders and agencies can serve as “referral sources”, especially the ubiquitous medical first aid station. Individuals in need may present to the booth through them or on their own, but case finding will likely be essential. And, throughout, the disaster psychiatrist should be sure to wear an identification badge that clearly identifies them as a psychiatrist so as not to “ambush” anyone. The outreach can run the gamut from asking someone how they are feeling while the psychiatrist hands out blankets (acting in the role of a fellow community member) or checks blood pressure (acting in the role of a physician) or while casually joining them over coffee or a meal at the food service areas that are usually set up in disaster assistance centers. All of these non-psychiatric encounters present opportunities to perform informal mental health screening, but such outreach can be challenging and may not fit every psychiatrist's comfort level.

Inherent in this shift of professional identity is a shift in technique. In the acute aftermath of a disaster, “treatment” is not the order of the day. Instead, disaster psychiatrists, and anyone wishing to work in a psychologically minded manner, should operate within the evidence-informed framework known as psychological first aid (PFA) 4)16). Adjusting to working within PFA presents another challenge to psychiatrists because it focuses on promoting coping and adaptation to traumatic circumstances and ideally is the vehicle for the earlier mentioned chance to prevent the very mental health conditions that psychiatrists have much more experience and comfort with treating after their onset. The following are the elements of PFA according to the U. S. National Institutes of Mental Health16):

1. Provide for basic needs

2. Protect from further harm

3. Reduce agitation & arousal

4. Support those in most distress

5. Keep families together and provide social support

6. Provide information, foster communication & education

7. Orient to available services

8. Use effective risk communication techniques

These very much reflect Maslow's theory on the hierarchy of human motivation and needs, but many PFA elements do not reflect standard psychiatric practice. Less important than the specifics of psychological first aid is its ethos, which is distinctly practical, calling for us to roll up our sleeves and not necessarily get out our prescription pads. Non-mental health professionals can be oriented to PFA in order to help them think about the psychological impact of the many non-psychological activities they undertake (i.e., handing out blankets to shivering tsunami survivors), in a sense, helping them to think of what they do at higher level. On the other hand, PFA often requires psychiatrists to operate at a “lower level” than they are accustomed to in order to achieve psychological ends while accomplishing practical ones.

As considerable psychological benefit may be derived from non-psychological interventions in the post-disaster setting, the disaster psychiatrist may need to lay down their psychological tools or at least put them at the bottom of their toolbox and focus on practical interventions. This can be highly challenging for some psychiatrists, and for those who seek to work through this possible struggle, PFA reminds us that even if we are not utilizing our usual psychological tools as we normally would, this does not mean we forgo our psychological mindset.

Before technique comes assessment, and here the challenge for psychiatrists lies in working in what is largely a pre-diagnostic framework. In the acute aftermath of a disaster, reactions to the event are hopefully far more adaptive than otherwise, as much of the distress survivors and other members of the disaster affected community experience will likely be expectable and healthy. To the extent that some of this distress is excessive and dysfunctional, it is most likely to come in the form of symptoms rather than diagnoses. Not only are many if not most people resilient, but there is also simply not enough time for symptoms to meet the duration criteria of our diagnostic criteria, at least for new onset disorders (and unlike recurrent disorders, which can manifest in this time frame). These can come in the form of emotional, cognitive, physical, and behavioral reactions12). Indeed, as much as psychiatrists are trained to base their ministrations around diagnoses, coming into the disaster scene primed to diagnose survivors not only ensures needless and even harmful pathologizing, but also constitutes terrible public relations for the field of psychiatry.

There is unfortunately no perfect answer to how to work pre-diagnostically. One interesting but yet-to-be adopted method is to consider acute, clinically significant post-traumatic distress a “stress injury”, for which the causative stressor is identified as either trauma, fatigue, or grief8). This approach addresses the clinical significance of disaster-related distress without pathologizing it, much like a broken bone resulting from an earthquake-induced collapse of a home needs a doctor but is not considered pathology. On the other hand, a more conventional approach to diagnosis may be to use the diagnosis of Adjustment Disorder from the DSM-V, which involves the “development of emotional or behavioral symptoms in response to an identifiable stressor (s) occurring within three months of the onset of the stressor (s).”2) A third and probably best option at this time is to simply avoid diagnosis and labelling, and to name the symptoms requiring clinical attention.

For clinically significant distress that falls short of diagnostic criteria for the common post-traumatic disorders or any other major psychiatric disorder identified in a disaster survivor, we should turn to Psychological First Aid. In all likelihood, the individuals most likely to come to the attention of a disaster psychiatrist and who are in most need of doing so are those in greatest distress. The psychiatrist trying to apply the PFA techniques of reducing agitation and arousal, and attending to those in most distress will naturally consider using their traditional psychiatric tools, psychotropic medications and psychotherapy. However, there exists a lack of evidence for acute interventions for acutely traumatized individuals, whether from a disaster or otherwise. This is especially the case with acute psychopharmacotherapy, where a recent review of medications for preventing PTSD plainly stated, “We conclude that there are no pharmacological preventive interventions that are ready for routine clinical practice.”9) On the other hand, there is no evidence to support the oft-cited clinical wisdom that giving medication to someone who has just been traumatized will interfere with natural healing.

As there is neither good evidence for or against prescribing, experience can potentially guide the acute use of medications. In our psychiatric outreach to individuals affected by the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York City, we relied on donations of the anxiolytic, lorazepam, and the hypnotic medication, zaleplon17). Choice of the former was based on experience of lorazepam being a medication that is flexibly used for both anxiety and insomnia and having the added advantage of minimal drug-drug interactions. Zaleplon became available as a chance donation from a pharmaceutical company. In the approximately 2 1/2 months where we were working at the Family Assistance Center established by the city to address the range of New Yorkers' needs, we gave out short-term supplies of zaleplon to 250 individuals and of lorazepam to 199 individuals. The average number of pills dispensed was five. Although we were unable to systematically follow-up with the recipients to evaluate our impact, our clinical impressions were that these medications were overwhelmingly beneficial and well-tolerate and helped people to “get over the hump” and tamp down their distress. Indeed, the most evidence-informed recommendation that can be made is that prescribing short-term medications for anxiety or insomnia, at least for adults, can have an important impact, and that one should rely on clinical judgment and compassion when prescribing.

As for psychotherapy, there is more evidence, and it supports short-term interventions based around cognitive-behavioral or exposure psychotherapy delivered over approximately 4 weeks within 1-2 months of the event in most studies18). These can both offer secondary prevention that helps reduce the incidence of PTSD or shorten its duration. However, offering such psychotherapies poses logistical challenges, as they require ongoing contact with the disaster-affected individual and involve psychotherapy modalities that many psychiatrists may not be trained in.

A related issue is what to call the people whom disaster psychiatrists assist, as most are not seeking us out as announced “patients.” It would be a misnomer to call someone whom a disaster psychiatrist engaged in a conversation over coffee a patient. Thus far in this paper, we explicitly avoided mentioning “patients” wherever possible and instead referred to “individuals”, “individuals in need”, “survivors”, and “affected community members”. When do they become a patient? This happens once the psychiatrist decides that a more formal evaluation is needed and, of course, the individual consents to this transition. It is the time when the psychiatrist decides they need to put down their coffee and pick up their figurative pen. This can be captured in the rough rule that someone should become a patient when the psychiatrist decides that the usual anonymity of what we might call the “brief encounter” no longer suffices and they need to know their name as part of a “formal encounter.”

As some individuals may indeed need a formal encounter and turn out to have a mental health condition, they will require follow-up. Ensuring long-term follow-up is a necessity and a challenge even as the focus is on the immediate recovery from the disaster. Thought must be given to this because acute disaster psychiatry is inevitably a voluntary activity, and it usually takes place under transient and rapidly shifting circumstances and in temporary locations. In our experience, disaster psychiatrists usually have one or perhaps two contacts with recent disaster-affected individuals and do not engage in this work with the intention of providing long-term services. Thus, there are two choices: A system can be set up wherein disaster psychiatrists are able to take on these cases in their usual practices or clinics. However, this brings up the issue of reimbursement, which can be complicated depending upon the country and healthcare system. In a fee-for-service system, there is also the challenge of not appearing like “ambulance chasers” who seek to diagnose disaster survivors in order to build their practice. On the other hand, providing long-term care on a voluntary basis may simply not be sustainable despite its idealism. A second choice, although not necessarily to the exclusion of the first, is to establish linkages with existing mental health agencies in the community. We have seen examples of the voluntary model and the latter linkage model.

Ultimately, this raises the issue of the sustainability of the disaster psychiatry effort. This is both an individual issue and a systems issue. How long does the individual disaster psychiatrist wish to be involved, and can and should a system be set up with the view to the long-term? Answers to these questions are specific to the person and the community. To lend some perspective, the program we established in early 2002 to respond to the medical and mental health needs of 9/11 responders in New York City, now known as the World Trade Center Health Program, continues to this day, nearly 20 years after 9/11. As of early 2021, nearly 25,000 World Trade Center disaster responders have undergone at least one annual monitoring visit, which includes screening for 9/11-associated medical and mental health problems, and approximately 1,000 responders are screened every month (there are estimated to have been 40,000-80,000 responders at the WTC site). In the mental health treatment program that serves those responders who “screen in”, in a recent month there were over 50 new intakes, nearly 750 psychotherapy visits, and almost 250 medication management visits (unpublished data courtesy of Sandra Lowe, M. D. ). This program certainly underscores the potential need for long-term mental health follow-up and represents something of a “gold-standard” approach for how to do it, including pairing up mental health services alongside medical services in order to improve access and reduce stigma. However, this long-term mental health program was born of generous philanthropic funding and maintained on what is now long-term federal funding that arose out of enormous advocacy efforts by labor unions, elected officials, and others.

Whether through formal encounters immediately post-disaster or through long-term screening programs, such as what is offered at the World Trade Center Health Program, the mental health problems that are identified are unlikely to be due entirely to the disaster. They may be recurrences of prior mental health problems brought on by the stress or trauma or ongoing problems that went undiagnosed or untreated but come to attention in the aftermath of disaster due to worsening from the stress or trauma or simply due to better access to mental health services. Especially in the acute period, there may also be people who need continued medication such as among displaced residents following Hurricane Harvey in Texas20). As mentioned earlier, pre-existing mental health problems are among the many risk factors for having new or recurrent post-disaster mental health problems, as are pre-disaster problems in living. As such, and as important as psychiatrists' involvement in disaster response is, there is therefore much reason to believe that if psychiatrists and the entire community of mental health professionals were positioned to steer more efforts towards improving population mental health before any disaster occurs, the need for disaster psychiatry would be reduced12). Helping our communities to be mentally healthier will improve life on a day-to-day basis and in the rare chance of a disaster. Improving a community's pre-disaster mental health may be as impactful as addressing post-event issues. Even if this is not necessarily as exciting as disaster psychiatry, it is a practical and possibly even a moral challenge for psychiatrists and planners to think about whether and how to put their resources more towards everyday mental health rather than disaster mental health.

How much more investment in pre-disaster mental health will impact disaster mental health is a question that only research can answer, but there are considerable practical and ethical challenges to conducting research in disaster psychiatry. In a potential disaster psychiatry research agenda, no area needs more study than acute post-disaster/trauma interventions, especially the use of medications for primary prevention of post-traumatic sequelae such as PTSD. Considering the relative rarity and unpredictability of disasters, it has thus far been a nearly insurmountable challenge to have research protocols ready to be deployed in their immediate aftermath, especially for intervention studies. This requires that the protocols be sufficiently flexible for the many faces of disaster, that funding and resources are at the ready, and that the all-essential partnerships with emergency response agencies, which are already difficult to establish for purposes of service delivery, can also accommodate a research agenda that has no direct benefit for the members of a disaster affected community. In addition, there lies the dubious ethics of conducting intervention research with the rigor of double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in such a vulnerable population as recent survivors of a disaster. For example, when someone has lost their home and most of their earthly possessions in a flood, how free would they be to decline participation in research that provides compensation and, on the other hand, how likely would such individuals be to sign unto un-compensated research when they are focused on the basic survival of their family? Much more imagination and foresight will be required if we are ever to gather empirical evidence for disaster psychiatric interventions that is the equal of the good will of disaster psychiatrists.

III. Personal Challenges

Thus far we have enumerated the many professional challenges of practicing disaster psychiatry. Before closing, some personal challenges are also worth mentioning. These include suddenly finding oneself working in an unfamiliar setting, including both the physical environment and interpersonal milieu. The atmosphere is far removed the characteristic tranquility and orderliness of the psychiatrist's office. As discussed earlier, the teamwork and collaboration of being part of a disaster response can be invigorating, but not necessarily for everyone-for some it can be overwhelming or frustrating.

Disaster zones are by their very nature marked by physical deprivations and emotional intensity, making for uniquely challenging working and living conditions. Extreme temperatures, inconsistent cell phone connectivity, scarce food, and, if the disaster psychiatrist is responding far from their own community, spartan sleeping accommodations may be too personally distressing to allow the psychiatrist to be effective at managing others' distress. The emotional intensity of the setting can also constitute direct trauma for the psychiatrist. With the possible exception of emergency psychiatrists, psychiatrists are normally accustomed to seeing trauma survivors at a time far removed from the incident. All psychiatrists minister to survivors at a physical distance from the scene of a trauma. There is always the risk of vicarious trauma in general psychiatric practice, but this is unlike the risk of the direct trauma of being at the scene of the incident, let alone so soon afterwards.

Lastly, the disaster psychiatrist will encounter the promise and peril of the media. A major disaster invites major media coverage. This can be an exciting chance to step out of the relatively reclusive world of psychiatric practice into the spotlight and an opportunity to be an ambassador for psychiatry and help many at once with carefully chosen words, but under the bright heat of klieg lights, psychiatrists can step into a minefield of misstatements. For example, the press and the public inevitably hunger for personal stories of survivors, and the psychiatrist may jeopardize the confidentiality of their encounters with survivors in trying to feed this appetite.

Conclusion

The challenges of disaster psychiatry far outnumber the rewards, but for many psychiatrists, the depth of the rewards more than compensate for this disparity. A potential reward(s) lies in every single challenge. A good way to forecast whether disaster work suits a psychiatrist's style or experience may be the following: As one reads through the list of challenges, do they feel excited or defeated? Ultimately, we do not need all psychiatrists to engage in disaster psychiatry, and most need to “maintain their posts” and keep addressing the vast mental health needs that exist in our every-day world apart from disasters. Everyone running towards a disaster is almost as bad as everyone running from it.

1) Alkire, S., Chen, L.: Global health and moral values. Lancet, 364 (9439); 1069-1074, 2004![]()

2) American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D. C., 2000

3) Angermeyer, M. C., van der Auwera, S., Carta, M. G., et al.: Public attitudes towards psychiatry and psychiatric treatment at the beginning of the 21st century: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. World Psychiatry, 16 (1); 50-61, 2017![]()

4) Brymer, M., Layne, C., Jacobs, A., et al.: Psychological First Aid Field Operations Guide, 2nd ed. 2006 (www.nctsn.org) (accessed April 17, 2021)

5) Cambridge Dictionary: Meaning of outreach in English. (https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/outreach) (accessed April 17, 2021)

6) Delisi, L.: The Acute Aftermath of an Earthquake in El Salvador. Disaster Psychiatry:Intervening When Nightmares Come True (ed by Pandya, A., Katz, C.). Analytic Press, Hillsdale, p.133-144, 2004

7) Doobay-Persaud, A., Adler, M. D., Bartell, T. R., et al.: Teaching the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med, 34 (5); 720-730, 2019![]()

8) Figley, C. R., Nash, W. P., eds: Combat Stress Injury: Theory, Research, and Management Routledge, New York, 2007

9) Frijling, J., Olff, M., van Zuiden, M.: Pharmacological prevention of PTSD: current evidence for clinical practice. Psychiatric Annals, 49 (7); 307-313, 2019

10) Garakani, A., Hirschowitz, L, Katz, C. L.: General disaster psychiatry. Psychiatr Clin North Am, 27 (3); 391-406, 2004![]()

11) Katz, C. L., Nathaniel, R.: Disasters, psychiatry, and psychodynamics. J Am Acad Psychoanal, 30 (4); 519-529, 2002![]()

12) Katz, C. L.: Disaster psychiatry: good intentions seeking science and sustainability. Adolescent Psychiatry, 1 (3); 187-196, 2011

13) Lindemann, E.: Symptomatology and management of acute grief. Am J Psychiatry, 101 (2); 141-148, 1944

14) Maslow, A. H.: A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50; 370-396, 1943

15) Merriam-Webster: Definition of outreach. (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/outreach) (accessed April 17, 2021)

16) National Institute of Mental Health: Mental Health and Mass Violence:Evidence-Based Early Psychological Intervention for Victims/Survivors of Mass Violence. A Workshop to Reach Consensus on Best Practices. NIH Publication, Washington, D. C., 2002

17) Pandya, A., Katz, C. L., Smith, R., et al.: Services provided by volunteer psychiatrists after 9/11 at the New York City Family Assistance Center: September 12- November 20, 2001. J Psychiatr Pract, 16 (3); 193-199, 2010![]()

18) Qi, W., Gevonden, M., Shalev, A.: Prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder after trauma: current evidence and future directions. Current Psychiatry Rep, 18 (2); 20, 2016![]()

19) Stoddard, F., Pandy, A., Katz, C. L., eds: Clinical Manual of Disaster Psychiatry American Psychiatric Press, Washington, D. C., 2011

20) Storch, E. A., Shah, A., Salloum, A., et al.: Psychiatric diagnoses and medications for Hurricane Harvey sheltered evacuees. Community Ment Health J, 55 (7); 1099-1102, 2019![]()

21) Stuart, H., Sartorious, N., Liinamaa, T., et al.: Images of psychiatry and psychiatrists. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 131 (1); 21-28, 2015![]()

22) Ursano, R. J., Fullerton, C. S., Weisaeth, L., et al.: Textbook of Disaster Psychiatry. Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017

23) Wikipedia: Humanitarianism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humanitarianism) (accessed April 17, 2021)